Receiving a cervical spine MRI report can feel like being handed a manuscript written in a foreign language. You see terms like "lordosis," "osteophyte," "thecal sac," and "foraminal stenosis," but you have no idea how they translate to the pain radiating down your arm or the stiffness in your neck. At Deuk Spine Institute, we believe that an educated patient is an empowered patient. You shouldn't have to wait for a brief appointment window to begin understanding what is happening inside your body.

This guide is designed to help you navigate the complex terminology of your radiology report. We will break down the anatomy, explain the different views you are looking at, and help you determine when findings might indicate a need for surgical intervention. Remember, we treat patients, not just MRIs. However, understanding your imaging is the first step toward reclaiming your life from back and neck pain.

The Basics: MRI Anatomy and Views of Cervical Spine Structures

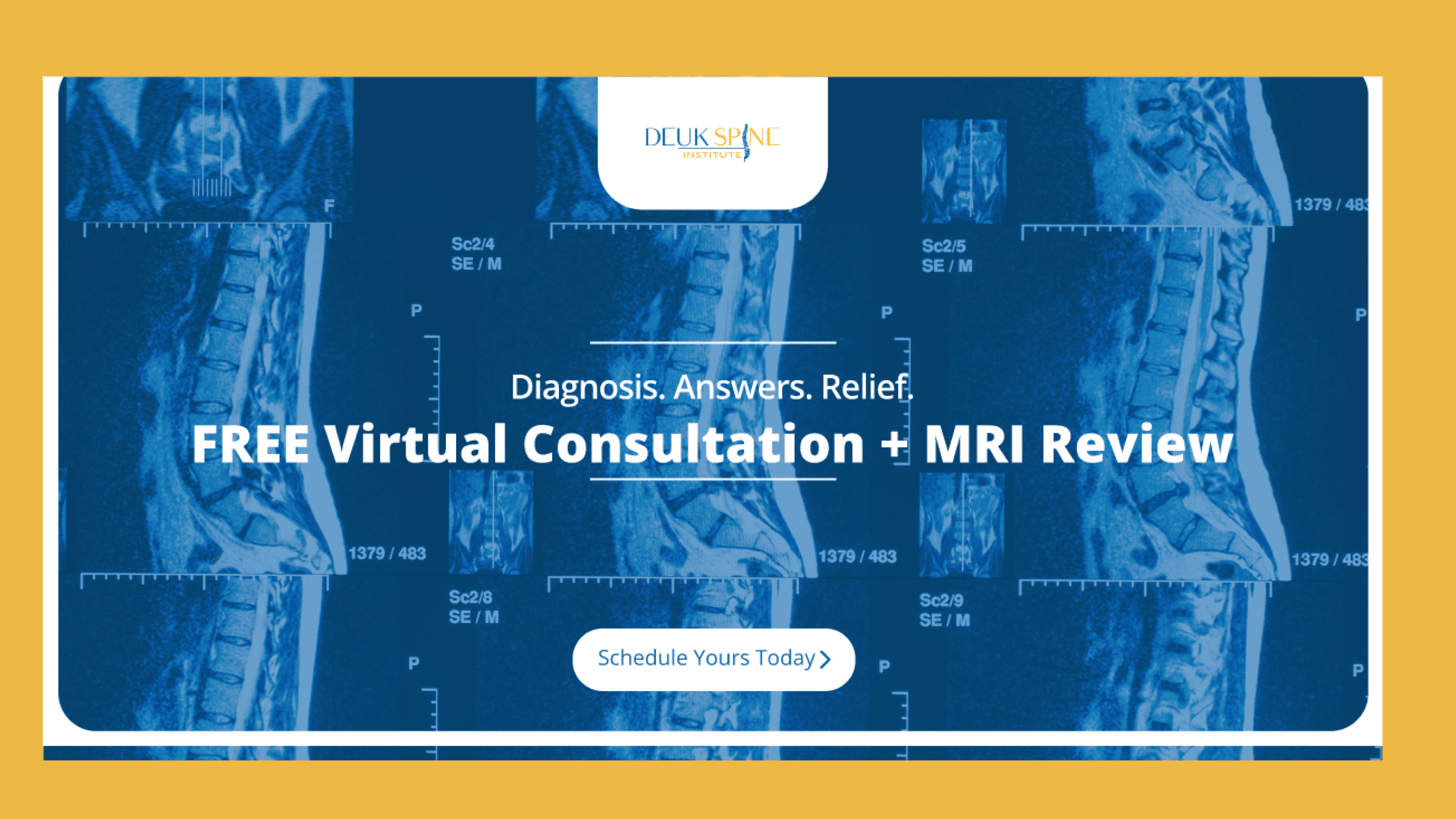

Before you can interpret pathology, you must understand the normal MRI anatomy and views of cervical spine structures. Your MRI is likely composed of two main views: Sagittal and Axial.

Sagittal Views: The Side Profile

The sagittal view shows your spine from the side, slicing it from left to right. This is the best view for assessing alignment and the height of your vertebral bodies and discs.

- Alignment: In a healthy neck, the vertebrae should form a gentle "C" shape curving inward, known as cervical lordosis. A loss of this curve (straightening) or a reversal (kyphosis) often indicates muscle spasms or structural instability.

- Vertebrae: These are the block-like bones stacked on top of each other. They should be rectangular and uniform in height.

- Discs: Between the vertebrae are the intervertebral discs. On a T2-weighted image (where water is bright), healthy discs should appear white or light gray in the center (nucleus pulposus) and dark around the edges (annulus fibrosus). Dark, flattened discs indicate dehydration and degeneration.

Axial Views: The Cross Section

The axial view shows your spine as if it were sliced horizontally, with the slice viewed from the feet looking up. This is critical for seeing the "donut" shape of the disc and the spinal canal.

- The Canal: In the center, you see the white circle of the spinal cord (or grey depending on the scan type) floating in cerebrospinal fluid.

- The Nerves: The nerve roots exit on the left and right. We look here to see if disc material or bone spurs are pinching these nerves as they leave the spine.

T1 vs. T2 Images

You will typically see "T1" and "T2" sequences.

- T2-Weighted Images: Water is bright. These are best for seeing the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) around the spinal cord and the hydration of your discs. Pathologies such as edema (swelling) or a herniated disc pressing on the white CSF are easiest to spot here.

- T1-Weighted Images: Fat is bright, and water is dark. These are useful for evaluating bone marrow and anatomy but are less distinct for detecting disc herniations than T2.

Explainer: Discogenic Neck Pain

For a deeper dive into the specific anatomy of the neck and how these structures interact, read our detailed breakdown of cervical spine anatomy, "Neck Pain 101: Understanding the Anatomy, Injuries, and Solutions." For more detail, watch "Discogenic Neck Pain."

Deciphering the Code: How to Read My Own Cervical Spine MRI Results

Reading cervical spine MRI results takes a systematic approach. Do not jump straight to the "Impression" section at the bottom, as it can be overwhelming. Instead, look at the body of the report where each level (e.g., C4-C5, C5-C6) is described individually.

Step 1: Check the Alignment

Look for terms like "anterolisthesis" or "retrolisthesis." This means that one vertebra has slipped forward or backward relative to another. This instability can stretch nerves and cause significant pain.

Step 2: Examine the Disc Height and Signal

Radiologists will note "disc desiccation" (drying out) or "loss of disc height." This confirms degenerative disc disease. While common with age, severe height loss puts stress on the facet joints behind the disc.

Step 3: Identify the "Herniation" Language

This is where the confusion often lies. You might see terms like bulge, protrusion, or extrusion.

- Bulge: A generalized expansion of the disc, like a tire low on air. It may or may not cause pain, depending on whether it touches a nerve.

- Herniation: A localized displacement of disc material. This is the "jelly" leaking out of the "donut."

- Mass effect: This means the herniation is large enough to push on the spinal cord or nerve roots, displacing them from their normal position.

If you see mention of a herniation, it is vital to know if it is compressing a nerve. We discuss this extensively in our article on diagnosing herniations.

Red Flags: Cervical MRI Findings That Indicate Surgical Consultation Needed

Not every abnormality on an MRI requires surgery. In fact, many people have bulging discs and no pain. However, there are specific cervical MRI findings that indicate the need for surgical consultation.

1. Cord Compression (Myelopathy)

If the report uses phrases like "cord flattening," "cord deformation," or "myelomalacia" (signaling change within the cord), this is serious. It means the spinal cord itself is being squashed. Unlike nerve roots, the spinal cord does not heal well. Compression here can lead to permanent paralysis, loss of balance, and loss of fine motor skills in the hands.

2. High-Grade Foraminal Stenosis

The "foramen" is the window through which the nerve exits the spine. "Severe" or "high-grade" stenosis means this window is shut, pinching the nerve. This often correlates with radiculopathy—pain, numbness, or weakness shooting down the arm.

3. Disc Extrusion with Free Fragment

This occurs when a piece of the disc nucleus breaks off entirely and floats in the spinal canal. These fragments can cause intense, acute chemical inflammation and mechanical compression.

If your MRI shows these features and you are experiencing weakness or severe pain, it is time to look beyond conservative care. Learn more about the symptoms associated with these specific levels in our guide to C4-C5 herniations.

Ready to find the root cause of your pain? Upload your MRI for a review by our spine experts.

The Silent Aggressor: Annular Tear Cervical Disc MRI Appearance and Meaning

One specific finding that is often overlooked by traditional spine surgeons but is a significant source of pain is the annular tear. The MRI appearance and meaning of an annular tear in the cervical disc are often described in reports as a "High Intensity Zone" (HIZ).

On a T2-weighted MRI, an annular tear appears as a bright white spot within the dark outer ring of the disc. This represents a rip in the annulus fibrosus. These tears are significant for two reasons:

- Leakage: They allow the toxic, inflammatory chemicals from the nucleus pulposus to leak out onto the nerves, causing chemical radiculitis (pain without compression).

- Structural failure: They are the precursor to a herniation.

Many surgeons ignore annular tears if there is no large herniation, yet these tears can be the primary source of chronic neck pain. If your report mentions an "annular fissure" or "HIZ" and you have persistent neck pain that traditional treatments haven't touched, you are likely suffering from discogenic pain.

Aging or Injury? Spondylosis Cervical Spine MRI Findings and Age-Related Changes

You will almost certainly see the word "spondylosis" in your report. Spondylosis of the cervical spine: MRI findings, age-related changes, essentially refer to "arthritis of the spine." It is a catchall term for the wear and tear that affects all of us.

Key signs of spondylosis include:

- Osteophytes (bone spurs): Your body grows extra bone to stabilize a worn-out joint. Unfortunately, these spurs can grow into the spinal canal or nerve windows.

- Facet hypertrophy: The joints on the back of the spine enlarge due to arthritis, taking up space in the canal.

- Ligamentum flavum hypertrophy: The ligament inside the spinal canal thickens/buckles, pushing into the spinal cord from behind.

While "mild spondylosis" is normal for anyone over 40, "moderate" to "severe" spondylosis can lead to spinal stenosis (narrowing of the canal). If your report mentions "central canal stenosis" less than 10-13mm, this is a critical finding that warrants expert review.

For a detailed look at how these degenerative changes progress and cause symptoms, refer to our article on radiculopathy.

The Big Question: Do I Need Surgery Based on My Cervical Spine MRI Results?

The short answer is: MRI results alone are never a reason for surgery.

We treat the patient, not the picture. You could have a terrible-looking MRI with multiple herniations and have zero pain. Conversely, you could have a small annular tear that is causing debilitating agony.

Surgery is indicated when:

- Findings match symptoms: Your MRI shows a C6 nerve compression, and you have pain/numbness in your thumb and index finger (the C6 dermatome).

- Neurological deficit: You have measurable weakness (e.g., foot drop or weak grip) or loss of reflexes.

- Failure of conservative care: You have tried rest, therapy, and medications, but the pain persists or worsens.

- Cord compression: As mentioned, spinal cord compression (myelopathy) often requires surgery to prevent permanent paralysis, even if pain is mild.

If you are being told you need a fusion (ACDF) based solely on "degenerative changes" without a clear correlation to your pain, we urge you to seek a second opinion. Fusion surgeries carry significant risks and often lead to adjacent segment disease. At Deuk Spine Institute, we focus on preserving your natural motion with Deuk Laser Disc Repair® whenever possible.

Remember, the MRI is a map. It shows us where the road is damaged. But only you can tell us if the ride is bumpy.

Make Your First Pain-Free Move

If you are seeking relief from neck pain, we can help improve your quality of life and enable you to live pain-free.

Upload your latest MRI for a free review and a personal consultation with myself, Ara Deukmedjian, M.D., founder of Deuk Spine Institute and creator of the Deuk Laser Disc Repair® procedure.

Watch Deuk Laser Disc Repair® in Action

Our goal is to be completely transparent about our process and procedures for treating neck issues. We livestream surgeries with our patients’ written consent, allowing you to observe our technique.

How One Man Overcame His Neck Pain with DLDR®.

FAQs

Q: Should I get a second opinion on cervical MRI interpretation?

A: Absolutely. Radiology reports are subjective and written by humans who may miss subtle findings like annular tears or foraminal stenosis. Furthermore, many surgeons may recommend invasive fusion surgery based on findings that could be treated with minimally invasive techniques. A second opinion, specifically from a neurosurgeon who reviews the actual images (not just the report), is crucial for ensuring you don't undergo unnecessary procedures.

Q: When should cervical spine MRI be repeated to check progression?

A: An MRI should generally be repeated if your symptoms change significantly (e.g., pain moves to a different arm, new weakness develops) or if 6-12 months have passed with persistent pain despite conservative treatment. Additionally, if you are considering surgery and your MRI is more than 6 months old, a new scan is usually required to ensure the roadmap is up to date.

Q: Comparing old and new cervical MRI reports the progression timeline.

A: Comparing old and new reports is the best way to distinguish "acute" (new) injuries from "chronic" (old) changes. If a disc herniation was present 5 years ago and hasn't changed, it is unlikely to be the source of new pain unless it has grown or calcified. However, rapid worsening of stenosis or new spinal cord edema (swelling) over a short time (months) indicates an aggressive process requiring immediate attention.

Q: Cervical MRI with and without contrast, which is better for diagnosis?

A: For most patients with neck pain or radiculopathy, an MRI without contrast is sufficient to see disc herniations and stenosis. Contrast (gadolinium) is typically reserved for patients who have had prior spine surgery (to distinguish scar tissue from a new herniation) or to rule out infection, tumors, or spinal cord cysts. Your doctor will determine if contrast is necessary based on your medical history.