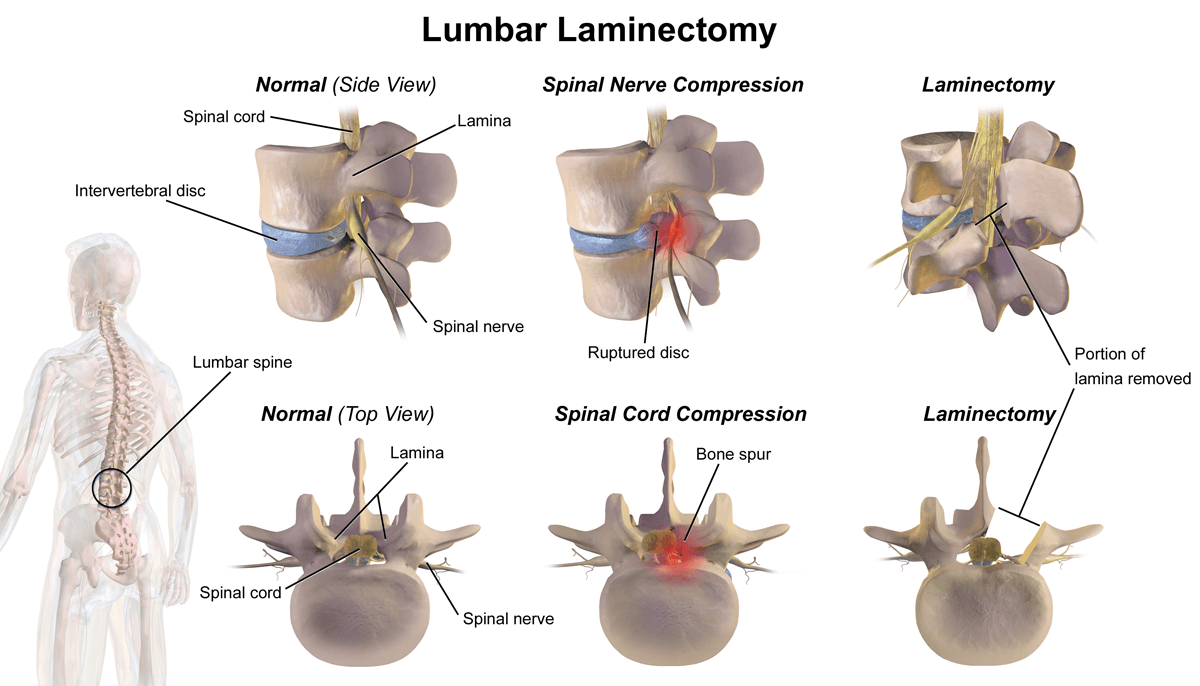

The primary purpose of a laminectomy, also known as decompression surgery, is to alleviate pressure on the spinal cord or the nerves that branch out from it by creating space with the removal of a portion of a vertebra called the lamina. This pressure, often referred to as compression, can cause pain, numbness, or weakness in your back, legs, or arms. By removing the lamina, the surgeon widens the spinal canal, giving the nerves more room and relieving the compression.

The primary indication for a laminectomy is spinal stenosis. This is a condition in which the spinal canal narrows, compressing the nerves within it. Spinal stenosis is often a result of age-related degenerative changes, such as the overgrowth of bone (bone spurs) or the thickening of ligaments. Other conditions that may be treated with a laminectomy include:

Herniated Discs: When the soft, gel-like center of a spinal disc pushes through a tear in its tough exterior, it can press on nearby nerves.

Nerve Compression from Tumors or Cysts: Growths within the spinal canal can compress the spinal cord or nerves, and a laminectomy may be necessary to remove them.

Degenerative Disc Disease: Over time, spinal discs can wear down, leading to the development of bone spurs and other changes that narrow the spinal canal, potentially causing compression of the nerves.

This article provides a detailed examination of spinal laminectomy. We will explore what the procedure entails, walk you through the surgical process, discuss potential complications, and explore alternative methods to relieve spinal pain without damaging tissues or requiring bone removal.

Four-Pronged Trauma

A laminectomy is a major surgery that involves carefully navigating the intricate structures of the spine. The procedure is typically performed under general anesthesia, meaning you will be asleep throughout the operation. That’s probably a good thing, since there’s a lot of trauma and destruction that happens while you sleep:

- Cutting Through the Fascia

The fascia, a tough connective tissue layer that surrounds and supports the muscles, must be incised to access the underlying structures.

Muscle Injury: The fascia provides structural support to the muscles. Cutting through it can disrupt this support, leaving the underlying muscles more vulnerable to trauma during the surgery. This can lead to muscle fiber injury, inflammation, or even atrophy (muscle wasting) if the muscles are not properly rehabilitated post-surgery. Patients may experience post-operative muscle weakness, soreness, or difficulty regaining full strength in the affected area.

Scar Tissue: Cutting through the fascia initiates a healing process that can result in the formation of scar tissue. Excessive scar tissue can adhere to surrounding structures, including muscles and nerves, potentially causing pain, stiffness, or restricted movement. This can lead to chronic discomfort or reduced flexibility in the back, potentially requiring physical therapy or additional interventions.

Impaired Healing: The fascia has a relatively poor blood supply compared to other tissues, which can slow down the healing process after it is cut. Delayed healing can increase the risk of complications, such as infection or prolonged post-operative pain. Patients may experience a more extended recovery period and a higher likelihood of complications like wound dehiscence (reopening of the surgical incision).

Loss of Structural Integrity: The fascia plays a key role in maintaining the structural integrity of the back by holding muscles and other tissues in place. Cutting through the fascia can weaken this support system, potentially leading to issues such as muscle herniation (where muscle tissue protrudes through the fascia) or instability in the affected area. This can result in chronic pain, reduced mobility, or the need for additional surgical repairs.

Increased Risk of Infection: Cutting through the fascia creates an entry point for bacteria, especially if the surgical site is not properly sterilized or if post-operative care is inadequate. An infection in the fascia or surrounding tissues can lead to complications like abscess formation or cellulitis (a bacterial skin infection). Infections can delay healing, cause significant pain, and may require antibiotics or additional surgical intervention.

Nerve Irritation or Damage: The fascia is closely associated with nerves that run through and around it. Cutting through the fascia can irritate or damage these nerves, either directly or through the formation of scar tissue.: This can result in nerve pain (neuropathy), numbness, or tingling in the affected area. Nerve-related symptoms can persist long after the surgery and may require specialized treatments like nerve blocks or physical therapy.

Chronic pain can result from damage to the fascia, leading to conditions such as myofascial pain syndrome, where trigger points (knots) develop in the muscles and fascia. This pain is often localized but can radiate to other areas, making it difficult to manage. Chronic pain can significantly affect a patient's quality of life and may require long-term pain management strategies.

Reduced Range of Motion: Cutting through the fascia can lead to stiffness and reduced elasticity in the tissue as it heals.This can limit the range of motion in the back, making it more difficult for patients to perform daily activities or return to their normal levels of physical activity. Physical therapy is often needed to restore flexibility and strength, but some patients may experience permanent limitations.

- Retraction of the Spinal Muscles

The large spinal muscles are then carefully retracted or moved aside, rather than cut, to expose the bony structure of the spine. In most modern laminectomy procedures, the spinal muscles (such as the erector spinae) are not cut but are instead retracted or moved aside to expose the vertebrae. However, this retraction can still cause some trauma to the muscle fibers, leading to post-operative soreness or weakness.

Muscle Strain or Injury: During retraction, the muscles are pulled aside and held in place for the duration of the surgery. This prolonged stretching can strain the muscle fibers. Patients may experience post-operative muscle soreness, stiffness, or even minor tears in the muscle tissue.

Ischemia (Reduced Blood Flow): Retracting the muscles for an extended period can compress blood vessels, reducing blood flow to the muscle tissue. Prolonged ischemia can lead to muscle damage or delayed recovery, causing weakness or pain in the affected area.

Nerve Irritation or Damage: The muscles in the back are closely associated with nerves. Retraction can put pressure on these nerves, leading to irritation or temporary dysfunction. Patients may experience numbness, tingling, or weakness in the areas served by the affected nerves. In rare cases, nerve damage can be permanent.

Muscle Weakness or Atrophy: Prolonged retraction or inadequate post-operative rehabilitation can weaken the muscles, leading to atrophy (muscle wasting). Patients may struggle to regain full strength and function in the affected muscles, which can affect their overall mobility.

Scar Tissue Formation: The trauma from retraction can trigger the formation of scar tissue in the muscles. Scar tissue can restrict muscle movement, leading to stiffness or chronic pain.

Chronic Myofascial Pain: Muscle retraction can irritate the fascia (the connective tissue surrounding the muscles), leading to chronic pain conditions like myofascial pain syndrome. Patients may develop trigger points (knots) in the muscles, causing localized or referred pain.

- Removal of a Key Ligament

Once the vertebra is visible, the surgeon begins the more delicate part of the procedure. The ligamentum flavum, a strong ligament that connects the laminae of adjacent vertebrae and helps protect the spinal cord, is removed. This step is crucial for accessing and decompressing the neural elements.

However, this removal can have several impacts on the spine's structure and function:

Loss of Spinal Stability: Removing the ligamentum flavum can reduce the spine's natural stability, potentially leading to spinal instability. This may cause abnormal movement between vertebrae, resulting in pain or even deformities, such as spondylolisthesis (slippage of one vertebra over another).

Post-Laminectomy Syndrome: The removal of ligaments, along with bone, can contribute to a condition known as post-laminectomy syndrome, where patients experience chronic pain or instability after surgery.

Altered Biomechanics of the Spine: Ligaments help control the range of motion and prevent excessive flexion, extension, or rotation of the spine. Without the ligamentum flavum, the biomechanics of the spine can change, potentially leading to increased stress on adjacent vertebrae and discs. Over time, this can contribute to adjacent segment disease, where the levels above or below the surgery site degenerate more quickly.

Risk of Scar Tissue Formation: The removal of ligaments can lead to the formation of scar tissue during the healing process. This scar tissue may compress nearby nerves, causing symptoms similar to those experienced before surgery.

Reduced Elasticity and Shock Absorption: This ligament is unique because it is highly elastic, allowing it to stretch and recoil during spinal movements. It also helps absorb shock and protect the spinal cord. Without the ligamentum flavum, the spine may lose some of its natural elasticity and shock-absorbing capacity, potentially leading to increased wear and tear on other spinal structures.

Increased Risk of Spinal Fluid Leaks: The ligamentum flavum is located close to the dura mater, the protective covering of the spinal cord. During its removal, there is a risk of accidentally puncturing the dura, which can lead to a cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leak. CSF leaks can cause headaches, nausea, and an increased risk of infection, such as meningitis.

- Removal of Bone and Facet Joints

The primary focus of a laminectomy is the removal of the lamina, which is the back part of the vertebra that forms the roof of the spinal canal. This creates more space within the spinal canal, thereby relieving nerve compression. Using specialized surgical tools, such as high-speed burrs or rongeurs, the surgeon carefully removes the lamina bone. In many cases, this also involves disrupting or completely removing the facet joint capsules. The facet joints link the vertebrae together and provide stability and flexibility to the spine.

This removal of bone can cause even more debilitating issues:

Spinal Stability: Removing too much bone can compromise spinal stability. In such cases, the surgeon may perform a spinal fusion to stabilize the affected area. The body does not regenerate the removed bone, but the surrounding tissues adapt to the changes over time.

Nerve Damage: The process of removing bone, especially near the spinal cord and nerve roots, carries a risk of accidental nerve injury. This can occur if the tools used for bone removal come too close to the delicate neural structures. Nerve damage can result in persistent pain, numbness, weakness, or even paralysis in severe cases.

Spinal Fluid Leaks: During bone removal, the dura mater (the protective covering of the spinal cord) can be accidentally punctured, leading to a cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leak. CSF leaks can cause headaches, nausea, and an increased risk of infection, such as meningitis.

Post-Laminectomy Syndrome: This is a condition where patients continue to experience pain after the surgery, despite the removal of bone and decompression of nerves. It can result from incomplete decompression, scar tissue formation, or spinal instability. The impact may be chronic pain and reduced quality of life.

Infection: Bone removal creates an open surgical site, which increases the risk of disease in the bone (osteomyelitis) or surrounding tissues. Infections can delay healing and may require antibiotics or additional surgery to address the issue.

Excessive Bleeding: The spine is surrounded by a rich network of blood vessels. Bone removal can sometimes damage these vessels, leading to significant blood loss. Excessive bleeding can complicate the surgery and prolong recovery.

Scar Tissue Formation: The removal of bone and the healing process can lead to the formation of scar tissue around the surgical site. Scar tissue can compress nerves, leading to pain or other symptoms similar to those experienced before surgery. Physical therapy and anti-inflammatory medications may help, but severe cases might require additional surgery.

Adjacent Segment Disease: Removing bone and altering the biomechanics of the spine can place additional stress on the vertebrae and discs above or below the surgical site. This can lead to the degeneration of adjacent spinal segments over time, resulting in the development of new symptoms.

Bone Regrowth (Spinal Stenosis Recurrence): In some cases, the bone may regrow over time, leading to a recurrence of spinal stenosis or nerve compression. This can result in the return of symptoms, such as pain, numbness, or weakness.

Reduced Range of Motion: Removing parts of the lamina and facet joints can alter the spine's natural movement and flexibility, resulting in a reduced range of motion. Patients may experience stiffness or a reduced range of motion in the affected area.

View the Destruction: a Laminectomy Surgery

Deuk Laser Disc Repair: The Better Way

If a laminectomy has been recommended to relieve your pain, there’s a better way - Deuk Laser Disc Repair (DLDR). This revolutionary procedure is Deuk Spine Institute’s specialized alternative to dangerous and destructive invasive surgeries like the laminectomy. DLDR does not compromise your health because there is no cutting of the fascia, no retraction of the muscles, no ligament removal, or bone removal.

A Game-changing Procedure

Created and performed exclusively by A. Deukmedjian, M.D., Deuk Laser Disc Repair (DLDR) is a minimally invasive form of endoscopic spine surgery conducted in a state-of-the-art surgery center under sedation, allowing patients to relax during the procedure. The procedure is done endoscopically using a high-definition camera inserted through a tiny 4mm incision to view the injured area.

DLDR uses a precision laser to vaporize the herniated tissue. Fascia, muscles, ligaments, or bone are not damaged or removed. Fusions and artificial discs are not necessary. After surgery, patients wake up to immediate relief and a surgical scar so small that the surgeon can cover it with a Band-Aid.

Watch Deuk Laser Disc Repair in Action

Our goal is to be completely transparent about our process and procedures for treating back issues. We livestream surgeries with our patients’ written consent, allowing you to observe our technique.

Make the First Move to Move Pain-Free

Upload your latest MRI for a free review and a personal consultation with acclaimed spinal surgeon Dr. Ara Deukmedjian, M.D., founder of Deuk Spine Institute and creator of the Deuk Laser Disc Repair® procedure. Our team will contact you to help you regain your life.