By Dr. Ara Deukmedjian, MD

Board-Certified Spine Surgeon, Deuk Spine Institute

Medically reviewed on December 29, 2025

Medical disclaimer: This content is for educational purposes only and does not constitute medical advice. Individual results may vary. Always consult with your healthcare provider about your specific conditions and treatment options.

Understanding a Common Source of Chronic Spinal Pain

Facet joint disease represents one of the most prevalent yet frequently misunderstood causes of chronic neck and back pain. Research indicates that facet joints account for 15% to 45% of cases of lower back pain, making them a significant contributor to spinal discomfort.1 Despite this high prevalence, many individuals suffer for years without receiving an accurate diagnosis or understanding why conventional treatments have failed to provide lasting relief.

The challenge in diagnosing and treating facet joint disease stems from several factors. First, facet-related pain often develops gradually over time, making it difficult for patients to identify a specific inciting event. Second, symptoms frequently overlap with other spinal conditions such as disc herniation or spinal stenosis, leading to diagnostic confusion. Third, imaging studies alone cannot definitively confirm that facet joints are the source of pain, requiring specialized diagnostic procedures for accurate identification.

As a board-certified spine surgeon with extensive experience treating facet joint pathology, I have observed that patients who receive proper diagnosis and targeted treatment can achieve remarkable improvements in pain relief and functional capacity. This comprehensive guide explores the anatomy and function of facet joints, the mechanisms by which disease develops, clinical presentation and diagnostic approaches, the full spectrum of treatment options from conservative to surgical, and when advanced interventions become necessary.

Understanding the nature of your spinal condition empowers you to make informed decisions about your care and advocate effectively for appropriate treatment.

30 Causes of Back Pain

In this short video Dr. Deukmedjian covers the 30 structural causes of back pain including facet joints.

The Anatomy and Function of Facet Joints

To properly understand facet joint disease, we must first examine the structure and role of these essential spinal components.

Structural Anatomy

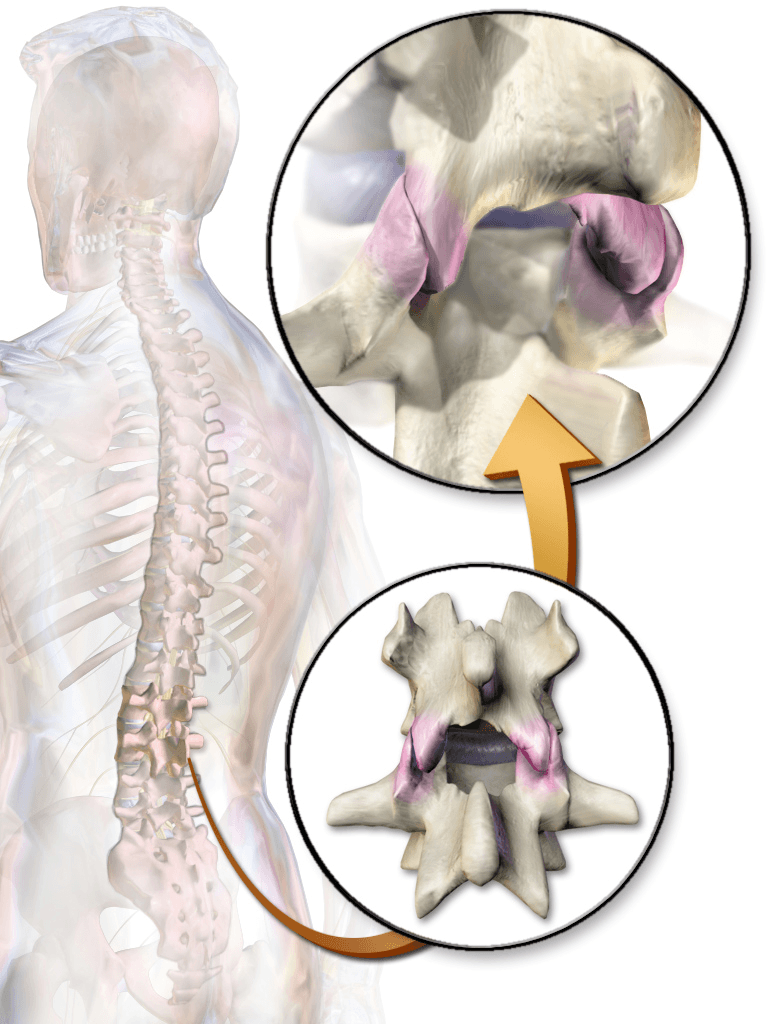

Facet joints, also known as zygapophyseal joints, are paired synovial joints located at the posterior aspect of the spine. At each spinal level, two facet joints connect the vertebra above to the vertebra below. These joints are formed by the articulation of paired bony projections called articular processes, which extend from the back of each vertebra.2

Together with the intervertebral disc, the two facet joints at each level form what is known as the “three-joint complex” or motion segment. This tripod configuration provides mobility and stability to the spinal column.1

The surfaces of the articular processes are coated with smooth articular cartilage, similar to that of other synovial joints, such as the knee or hip. This cartilage facilitates frictionless movement between adjacent vertebrae. The joint surfaces are encapsulated by a thin synovial membrane that produces synovial fluid, which lubricates the joint and nourishes the cartilage.

Surrounding the synovial membrane is a robust outer capsule composed of dense fibrous tissue. This capsule is tough yet slightly flexible, allowing for movement while providing structural integrity. The capsule contains approximately 2 milliliters of joint fluid and is richly innervated with sensory nerve fibers, making it a potential source of pain when damaged or inflamed.

Small fat pads adjacent to the facet joints move in and out of the joint space during spinal motion, providing additional lubrication and cushioning. The spinal nerves exit the spinal canal just above the upper facet joint at each level, placing them in close proximity to these structures and making them vulnerable to compression if the facet joints become enlarged or malpositioned.

Biomechanical Functions

Facet joints serve multiple critical functions in spinal biomechanics:

Guiding spinal motion: The orientation and shape of facet joints determine the direction and degree of movement possible at each spinal level. In the lumbar spine, facet joints are oriented more sagittally, allowing significant flexion and extension (forward and backward bending) while limiting rotation. This protects the intervertebral discs from excessive rotational forces that could cause injury. The cervical facets are oriented more coronally, permitting greater rotational movement necessary for head turning.

Load distribution: During both static postures and dynamic movements, facet joints absorb and distribute compressive and shear forces applied to the spine. This load-sharing function protects other spinal structures, particularly the intervertebral discs, from excessive stress. Studies have demonstrated that facet joints bear approximately 16% of the axial load in neutral posture, but this percentage increases significantly during extension movements.3

Preventing excessive motion: Facet joints act as mechanical stops, preventing the vertebrae from moving beyond safe ranges. This protective function prevents hyperextension, excessive rotation, and forward slippage of vertebrae that could damage discs, compress nerve roots, or injure the spinal cord.2

Proprioceptive function: The rich innervation of facet joint capsules contributes to proprioception—the body’s ability to sense its position in space. This sensory feedback helps coordinate movements and maintain proper posture. The medial branch nerves that supply sensation to the facet joints transmit important information about spinal position and movement to the central nervous system.

Regional variations: The anatomy and function of the facet joints vary across spinal regions. Lumbar facet joints, particularly at the L4-L5 and L5-S1 levels, bear the greatest loads as they support the weight of the entire upper body. This makes these lower lumbar facets particularly susceptible to degenerative changes and injury. Cervical facet joints accommodate greater rotational demands due to the mobility requirements of the head and neck.

What Is Facet Joint Disease?

Facet joint disease, also referred to as facet arthropathy, facet syndrome, or facet joint osteoarthritis, encompasses a spectrum of pathological conditions affecting these spinal joints. The condition involves progressive degeneration, inflammation, and structural changes within the facet joints that ultimately lead to pain and functional impairment.

Pathophysiological Mechanisms

Cartilage degeneration: Like other forms of osteoarthritis, facet joint disease begins with the breakdown of articular cartilage. The smooth cartilage that normally covers the joint surfaces gradually deteriorates, losing water content and structural integrity. This process is mediated by an imbalance between cartilage synthesis and degradation, involving complex interactions of inflammatory cytokines, proteolytic enzymes, and mechanical factors.2

As cartilage thins and becomes irregular, the protective cushioning between bones diminishes. This leads to increased friction during movement and altered load distribution across the joint surfaces. Eventually, areas of cartilage may be lost entirely, resulting in bone-on-bone contact.

Synovial inflammation: The synovial membrane lining the joint capsule becomes inflamed in response to cartilage breakdown products and altered joint mechanics. This synovitis produces inflammatory mediators that sensitize pain nerves within the joint capsule and contribute to ongoing tissue damage. The inflamed synovium may produce excess fluid, causing joint effusion and capsular distension.3

Subchondral bone changes: As cartilage degenerates, the underlying bone (subchondral bone) undergoes reactive changes. The bone may become sclerotic (abnormally dense) in areas of increased stress. Subchondral cysts may develop, and the bone surfaces may become irregular. These bony changes alter joint biomechanics and contribute to pain generation.4

Osteophyte formation: The body responds to joint instability and abnormal motion by forming bony spurs called osteophytes at the margins of the facet joints. While osteophytes represent an attempt to stabilize the joint, they can cause problems by encroaching on the spinal canal or neural foramina (the openings through which spinal nerves exit). This may result in spinal stenosis or nerve root compression.5

Capsular changes: The fibrous joint capsule may become thickened, fibrotic, and less flexible over time. The capsule may also develop areas of weakness or tearing, particularly with acute injury or chronic stress. Because the capsule is richly innervated with pain-sensitive nerve fibers, capsular pathology is a significant source of facetogenic pain.3

Ligamentous hypertrophy: The ligamentum flavum, which connects adjacent vertebrae posteriorly near the facet joints, commonly becomes thickened and calcified in association with facet joint disease. Ligamentous hypertrophy can contribute to spinal canal narrowing and nerve compression.2

The Relationship Between Disc and Facet Degeneration

For many years, facet joint degeneration was viewed as a consequence of disc degeneration. According to this traditional model, disc height loss causes the vertebrae to approximate, increasing stress on the facet joints and leading to secondary facet arthropathy. However, emerging research has challenged this view.

Recent studies demonstrate that facet joint degeneration may actually precede disc degeneration in many cases, rather than simply being a consequence of it. Research indicates that the relationship between disc and facet pathology is bidirectional—each can influence the other, and both contribute to the overall degenerative cascade within the spinal motion segment.2

This understanding has important implications for treatment. Addressing only the disc pathology while ignoring concurrent facet disease may result in incomplete pain relief. Conversely, treating isolated facet pathology without considering disc involvement may likewise prove insufficient. A comprehensive evaluation of the entire motion segment is essential for optimal treatment planning.

Etiological Factors: Causes of Facet Joint Disease

Facet joint disease rarely develops from a single cause. Instead, it typically results from the cumulative effects of multiple contributing factors acting over time.

Age-Related Degeneration

Aging represents the most significant risk factor for developing facet joint disease. The prevalence of facetogenic pain increases substantially with advancing age, with studies demonstrating that older adult populations show significantly higher rates of facet-mediated pain compared to younger groups.6

The aging process affects facet joints through several mechanisms. Articular cartilage loses water content, reducing the activity of proteoglycan molecules that provide cushioning and shock absorption. Synovial fluid production may decrease, reducing joint lubrication. The capsular tissues become less elastic and more prone to injury. Cumulative microtrauma from decades of movement gradually wears down joint structures.

These age-related changes make facet joints increasingly vulnerable to symptomatic degeneration, though it is important to note that degenerative changes on imaging studies do not always correlate with pain. Many individuals demonstrate significant facet arthropathy on MRI or CT scans yet experience no symptoms whatsoever.

Intervertebral Disc Degeneration

As discussed previously, the intervertebral discs and facet joints function as an integrated unit. When disc height decreases due to degeneration, the biomechanics of the entire motion segment change. The vertebrae approximate (move closer), altering the orientation of the facet joints and changing how forces are distributed across these structures.

Disc bulging or herniation can shift the axis of rotation for spinal movements, placing abnormal stress on the facet joints. Over time, these altered biomechanics accelerate facet joint breakdown. Research has documented that patients with advanced disc degeneration frequently demonstrate concurrent facet joint pathology.7

Trauma and Injury

Both acute traumatic events and repetitive microtrauma can initiate or accelerate facet joint disease:

Acute trauma: Motor vehicle accidents, particularly those involving whiplash-type injuries, commonly damage facet joints. The rapid acceleration-deceleration forces can tear the facet joint capsule, damage cartilage, or even cause facet joint dislocation or fracture. Falls, especially those resulting in hyperextension injuries, similarly stress facet joints. Sports injuries involving contact, excessive extension, or rotational forces can acutely injure facet structures.2

Repetitive microtrauma: Occupational activities involving repetitive bending, twisting, or lifting place cumulative stress on facet joints. Workers engaged in heavy manual labor face elevated risks of developing symptomatic facet disease. Athletes in sports that require repetitive hyperextension—such as gymnasts, dancers, and football linemen—are particularly susceptible to facet joint problems. Even prolonged static postures, such as extended sitting with poor ergonomics, can chronically stress facet joints.3

Postural Factors and Spinal Alignment

Poor posture and spinal malalignment contribute significantly to facet joint stress:

Hyperlordosis: Excessive lumbar lordosis (swayback posture) increases facet joint loading during standing and walking. This posture compresses the facet joints, accelerating wear.

Scoliosis: Lateral curvature of the spine causes asymmetric loading of facet joints, with joints on the concave side of curves experiencing greater stress. This asymmetric loading accelerates degenerative changes on the more heavily loaded side.

Kyphotic deformities: Excessive thoracic kyphosis or loss of normal cervical lordosis alters the biomechanics of adjacent spinal regions, potentially overloading certain facet joints.

Leg length discrepancy: Differences in leg length create pelvic obliquity, which transmits asymmetric forces through the lumbar spine and facet joints.8

Spinal Instability

Conditions that create abnormal motion or instability within spinal segments accelerate facet joint degeneration:

Spondylolisthesis: When one vertebra slips forward relative to the vertebra below (degenerative spondylolisthesis), the facet joints at that level experience abnormal stress patterns. The joints must accommodate altered motion mechanics while simultaneously providing stability, which accelerates degeneration. Research demonstrates a clear association between facet joint orientation and the development of degenerative spondylolisthesis.3

Facet tropism: Asymmetry in the orientation of the left and right facet joints at the same spinal level—termed facet tropism—has been investigated as a potential risk factor for both facet arthritis and disc degeneration. While some studies have suggested that significant tropism creates unbalanced forces that accelerate degeneration, other research has not confirmed this relationship. The role of tropism remains an area of ongoing investigation.9

Inflammatory Conditions

While most facet joint disease represents mechanical degeneration (osteoarthritis), inflammatory arthropathies can also affect facet joints:

Rheumatoid arthritis: This systemic autoimmune condition can cause inflammatory arthritis in facet joints, particularly in the cervical spine.

Ankylosing spondylitis: This inflammatory condition primarily affects the spine and sacroiliac joints, leading to inflammation of the facet joints that may eventually result in fusion.

Other seronegative spondyloarthropathies: Conditions such as psoriatic arthritis and reactive arthritis can involve facet joints as part of their systemic manifestations.2

Genetic and Constitutional Factors

Emerging evidence suggests that genetic factors influence individual susceptibility to facet joint disease. Variations in genes encoding cartilage structural proteins, inflammatory mediators, and matrix-degrading enzymes may predispose certain individuals to earlier or more severe facet degeneration.

Body weight and body mass index also influence facet joint stress, with obesity increasing mechanical loading on lumbar facet joints and accelerating degenerative processes.

Clinical Presentation: Recognizing the Symptoms of Facet Joint Disease

The symptoms of facet joint disease vary depending on the location of affected joints, the severity of degeneration, and whether adjacent neural structures are involved.

Lumbar Facet Joint Disease

The lumbar spine, particularly the lower levels at L4-L5 and L5-S1, represents the most common site of symptomatic facet joint disease.

Axial low back pain: Patients typically describe a deep, aching pain localized to the lower back. The pain is often unilateral if only one facet joint is affected, but may be bilateral if both facets at a spinal level are involved. The quality of pain is generally described as dull and aching rather than sharp or burning.1

Pain characteristics: Facet-mediated pain characteristically worsens with specific movements and positions. Extension (backward bending), prolonged standing, and rotational movements typically exacerbate symptoms. Many patients report that their pain is worse upon arising in the morning, improves with gentle activity as the joints “warm up,” then worsens again with prolonged activity or at the end of the day.

Sitting, particularly in a slightly flexed posture, often provides relief because this position unloads the facet joints. Patients may report that lying down reduces their pain, though sleeping in certain positions (particularly prone with the back extended) may be uncomfortable.

Referred pain patterns: Facet joint pain commonly refers to regions beyond the immediate site of pathology. Lumbar facet joints most frequently refer pain to the buttocks, hips, and posterior or lateral thighs. Research mapping facet joint pain patterns demonstrates that lumbar facet pain rarely extends below the knee, which helps distinguish it from radicular pain caused by nerve root compression.6

The L1-L2 facet joints typically refer pain to the upper lumbar region and flank. The L2-L3 joints refer to the lateral hip and upper lateral thigh. The L3-L4 joints produce pain in the buttocks and lateral thigh. The L4-L5 facets refer pain to the posterior and lateral buttocks, posterior thigh, and lateral leg. The L5-S1 joints commonly produce buttock and posterior thigh pain.

It is important to recognize that these referral patterns show considerable overlap, and pain distribution alone cannot definitively identify which specific facet joint is the pain generator.

Associated symptoms: Patients may report stiffness and reduced range of motion, particularly with extension and rotation. Some individuals describe a sensation of the back “catching” or “locking” during certain movements. Muscle spasm in the paraspinal muscles is common as these muscles contract protectively in response to facet joint inflammation.

In cases of advanced degenerative changes with osteophyte formation, patients may perceive a grinding, clicking, or popping sensation during spinal movement. Palpation over the affected facet joint typically elicits localized tenderness.

Cervical Facet Joint Disease

Facet joint pathology in the cervical spine produces distinct symptom patterns:

Neck pain: Similar to lumbar facet disease, cervical facet disease causes deep, aching neck pain. The pain is typically worse with neck extension and rotation. Patients often report difficulty with activities requiring sustained neck positioning, such as looking upward or sleeping.

Referred pain patterns: Cervical facet joints exhibit well-characterized referral patterns, as mapped through experimental injection studies. The C2-C3 facet joint can refer pain to the suboccipital region and the upper posterior neck. The C3-C4 joint produces pain that extends into the lower posterior neck and the upper trapezius region. The C4-C5 facet refers pain to the upper back and shoulder region. The C5-C6 and C6-C7 joints can refer pain to the periscapular region and even into the upper arm.6

Headaches: Cervical facet joint disease, particularly involving the upper cervical levels, is a common cause. Cervicogenic headaches typically originate at the base of the skull and may radiate forward toward the temples or behind the eyes. They are often unilateral and may be associated with neck stiffness and reduced cervical range of motion.8

Neurological symptoms: While facet joint disease itself does not directly compress nerve roots, osteophyte formation and joint hypertrophy can narrow the neural foramina through which cervical nerve roots exit. This may produce radicular symptoms, including arm pain, numbness, tingling, or weakness following specific dermatomal patterns.

Thoracic Facet Joint Disease

Though less common than lumbar or cervical facet pathology, thoracic facet joint disease presents unique diagnostic challenges:

Pain location: Thoracic facet pain is typically experienced in the mid-back region but may refer to unexpected locations. Thoracic facet joints can refer pain around the ribcage to the anterior chest wall, mimicking cardiac or pulmonary conditions. Pain may also refer to the flank or even produce abdominal discomfort.10

Breathing-related symptoms: Because rib articulations lie close to the thoracic facet joints, some patients experience pain with deep breathing, coughing, or sneezing. This can raise concerns about pulmonary pathology and may lead to extensive cardiac and pulmonary workups before the spinal source is identified.

Diagnostic challenges: The atypical referral patterns of thoracic facet joints frequently lead to delayed or missed diagnoses. Patients may undergo extensive evaluation by cardiologists, pulmonologists, or gastroenterologists before the facetogenic source of their symptoms is recognized.10

Diagnostic Evaluation: Establishing an Accurate Diagnosis

Diagnosing facet joint disease requires a multimodal approach that combines clinical assessment, imaging studies, and, often, diagnostic injections.

Clinical History and Physical Examination

The diagnostic process begins with a thorough clinical evaluation. Key historical elements include pain location and referral patterns, activities and positions that worsen or relieve symptoms, temporal patterns such as morning stiffness, history of trauma or occupational risk factors, and response to previous treatments. Physical examination includes several important components:

- Inspection and palpation: Visual inspection may reveal postural abnormalities or paraspinal muscle spasm. Palpation over the facet joints, located approximately 1-2 centimeters lateral to the midline spinous processes, often elicits focal tenderness at the symptomatic levels.

- Range of motion testing: Active and passive range of motion is assessed in all planes. Facet-mediated pain typically worsens with extension and rotation. The facet loading test, performed by having the patient extend and rotate the spine while standing, reproduces facetogenic pain in many cases, though studies indicate this maneuver has limited sensitivity and specificity.1

- Neurological examination: A comprehensive neurological assessment evaluates motor strength, sensory function, and deep tendon reflexes throughout the relevant nerve root distributions. This helps determine whether nerve root compression is present in addition to facet joint pathology.

- Special tests: Various provocative maneuvers may suggest facetogenic pain, though none is definitively diagnostic. The extension-rotation test and Kemp’s test (combined extension, lateral bending, and rotation) are commonly employed.

Imaging Studies

Multiple imaging modalities contribute to the evaluation of facet joint disease, though it is crucial to recognize that imaging findings must be interpreted in the context of clinical symptoms.

Radiographs (X-rays): Standard anteroposterior, lateral, and oblique radiographs of the spine provide initial assessment of facet joint anatomy. Oblique views are particularly valuable for visualizing lumbar facet joints, which appear as the “Scottie dog” configuration. X-rays can demonstrate facet joint space narrowing, subchondral sclerosis, osteophyte formation, and gross malalignment such as spondylolisthesis.4

Flexion-extension radiographs assess for instability, demonstrating whether abnormal motion occurs between vertebrae during dynamic positioning. This can identify spondylolisthesis that is only apparent during weight-bearing or movement.

Computed tomography (CT): CT scanning provides superior visualization of bony anatomy compared to plain radiographs. The cross-sectional imaging capability of CT allows excellent assessment of facet joint morphology, articular surface irregularities, osteophyte size and location, subchondral cysts, and calcification of joint capsules or surrounding ligaments.

CT is considered the preferred imaging modality for evaluating facet joint osteoarthritis, particularly for grading severity using classification systems such as Pathria’s classification, which grades facet degeneration from grade 1 (joint space narrowing) through grade 3 (severe degenerative disease with narrowing, sclerosis, and osteophytes).4

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI): MRI provides excellent soft tissue contrast and can demonstrate joint effusions, synovitis, bone marrow edema within the facet joint, cartilage abnormalities, and capsular changes. MRI also allows comprehensive evaluation of associated pathology including disc degeneration, spinal stenosis, and nerve root compression.

However, like other imaging modalities, MRI findings of facet joint degeneration are common in asymptomatic individuals and do not prove that the facet joints are the pain source. Clinical correlation is essential.

Single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT): SPECT bone scanning can identify areas of increased metabolic activity and bone turnover. Increased uptake in facet joints may suggest active inflammation or stress, though this finding is not specific and must be interpreted cautiously.

Limitations of imaging: A critical principle in facet joint disease is that imaging abnormalities do not necessarily correlate with clinical symptoms. Numerous studies have documented a high prevalence of facet joint degeneration on imaging in completely asymptomatic individuals. Advanced facet arthropathy visible on CT or MRI does not prove that these joints are generating a patient’s pain. Conversely, relatively normal-appearing facet joints on imaging do not exclude facetogenic pain.9

Diagnostic Facet Joint Injections

Because imaging studies cannot definitively determine whether facet joints are the source of pain, diagnostic injections represent the gold standard for confirming facetogenic pain.

Medial branch blocks: The medial branch nerves are small sensory nerves that supply the facet joint capsules. Each facet joint receives sensory innervation from medial branch nerves arising at the spinal level of the joint and the level above. For example, the L4-L5 facet joint is innervated by the L3 and L4 medial branch nerves.

Medial branch blocks involve injecting local anesthetic around these nerves under fluoroscopic guidance. If the patient experiences significant pain relief (typically defined as greater than 80% reduction) following the injection, and this relief lasts for the duration of the local anesthetic’s action, this confirms that the blocked facet joint is a pain generator.1

Double-block paradigm: Because false-positive responses to single diagnostic blocks can occur in 25-40% of cases, many experts recommend confirmatory testing with a second block using a local anesthetic with a different duration of action. For example, an initial block with lidocaine (shorter acting) is followed on a separate day by a block with bupivacaine (longer acting). If the patient’s pain relief lasts for the expected duration of each anesthetic, this provides stronger evidence that the facet joint is the true pain source.1

Intra-articular facet joint injections: An alternative diagnostic approach involves injecting local anesthetic directly into the facet joint space rather than targeting the medial branch nerves. While this can provide diagnostic information, intra-articular injections are technically more challenging and may not accurately reflect pain relief from medial branch procedures. Research suggests medial branch blocks have advantages in terms of ease of performance and reproducibility.10

Find Out If Minimally Invasive is Right for You

Upload your latest MRI for a free consultation and review with Dr. Ara Deukmedjian.

Conservative Treatment Approaches

For the majority of patients with facet joint disease, initial management focuses on conservative, non-surgical interventions. These approaches aim to reduce inflammation, improve function, and provide symptomatic relief while minimizing treatment risks.

Pharmacological Management

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs): Medications such as ibuprofen, naproxen, and celecoxib reduce inflammation and provide analgesic effects. NSAIDs can be effective for managing facetogenic pain, particularly during acute exacerbations. However, long-term use requires monitoring for gastrointestinal, cardiovascular, and renal side effects.

Acetaminophen: While primarily analgesic rather than anti-inflammatory, acetaminophen provides a safer option for patients who cannot tolerate NSAIDs or who have contraindications to their use.

Muscle relaxants: Medications such as cyclobenzaprine, tizanidine, or methocarbamol can help relieve muscle spasms that often accompany facet joint pain. These agents are typically used for short-term management during acute flares.

Neuropathic pain medications: Although facet joint pain is not primarily neuropathic in nature, some patients benefit from medications such as gabapentin or pregabalin, particularly when referred pain patterns are prominent.

Topical agents: Topical NSAIDs, lidocaine patches, or capsaicin preparations may provide localized relief with minimal systemic side effects.

Oral corticosteroids: Short courses of oral prednisone or methylprednisolone can be beneficial during acute inflammatory episodes, providing more potent anti-inflammatory effects than NSAIDs alone.

Physical Therapy and Exercise

Structured physical therapy is a cornerstone of conservative management of facet joint disease. Therapeutic exercise programs address multiple aspects of the condition:

- Core strengthening: Exercises targeting the abdominal and paraspinal muscles provide dynamic spinal stabilization, reducing stress on the facet joints. Research demonstrates that core strengthening can improve pain and function in patients with facetogenic low back pain.

- Flexibility training: Stretching exercises for the hip flexors, hamstrings, and spinal extensors can reduce facet joint loading by improving overall spinal mechanics. Maintaining flexibility allows for a more balanced distribution of forces across spinal structures.

- Postural training: Education regarding proper posture during sitting, standing, and sleeping helps minimize facet joint stress. Patients learn to identify and avoid positions that exacerbate their symptoms.

- Manual therapy: Physical therapists may use manual techniques, such as joint mobilization, soft-tissue massage, and myofascial release, to reduce muscle spasm and improve mobility. While these techniques provide symptomatic relief, their effects on underlying facet joint pathology are limited.

- Activity modification: Therapists work with patients to identify aggravating activities and develop strategies to modify them. This might include ergonomic adjustments to workstations, proper lifting techniques, or guidance on appropriate exercise programs.

The effectiveness of physical therapy depends on patient adherence and consistency. Home exercise programs that patients can perform independently are essential for long-term success.2

Lifestyle Modifications

Weight management: For overweight or obese patients, weight loss reduces mechanical loading on the spine and decreases systemic inflammation. Even modest weight reduction can provide meaningful symptom improvement.

Smoking cessation: Tobacco use impairs tissue healing and increases systemic inflammation. Smoking cessation is strongly encouraged for all patients with spinal conditions.

Activity pacing: Learning to pace activities and avoid prolonged static postures helps prevent symptom flares. Patients benefit from taking regular breaks during sustained activities.

Sleep optimization: Proper sleep positioning and mattress selection can significantly impact symptoms. Sleeping in positions that minimize facet joint loading is important for many patients.

Interventional Pain Management Procedures

When conservative measures provide insufficient relief, interventional procedures may be considered:

Therapeutic intra-articular facet joint injections: Injection of corticosteroid medication directly into the facet joint can reduce inflammation and provide pain relief lasting weeks to months. While these injections do not address underlying structural pathology, they can facilitate participation in physical therapy and help patients regain function. Evidence for the long-term efficacy of intra-articular facet joint injections shows moderate support for both short-term and long-term pain relief in lumbar facet disease.11

Medial branch blocks with corticosteroids: Similar to diagnostic blocks, therapeutic medial branch blocks include corticosteroid medication in addition to local anesthetic. These injections target the nerves supplying the facet joints and can provide longer-lasting relief than intra-articular injections. However, like intra-articular injections, the effects are temporary, and repeat procedures may be necessary.1

Limitations of Conservative Treatment

While conservative management is appropriate as initial treatment for most patients with facet joint disease, these approaches have important limitations. Medications provide only symptomatic relief without addressing structural pathology. Physical therapy and exercise require significant patient effort and time commitment, and benefits may plateau. Injections offer temporary relief that typically diminishes over time, requiring repeat procedures. For some patients, conservative measures simply do not provide adequate relief despite optimal implementation.

When symptoms remain severe and functionally limiting despite appropriate conservative treatment over a period of several months, more definitive interventions may be warranted.

Surgical Treatment Options for Facet Joint Disease

Surgical intervention for facet joint disease is considered when conservative treatment has failed to provide adequate relief and when symptoms significantly impair quality of life. The decision to pursue surgery should be made carefully, with full understanding of the risks, benefits, and alternatives.

Traditional Surgical Approaches

Facetectomy: This procedure involves the surgical removal of all or part of the affected facet joint. Partial facetectomy preserves some joint structure and may maintain stability, while complete facetectomy removes the entire joint. Facetectomy is typically performed to decompress nerve roots that are compressed by hypertrophied facet joints or osteophytes.

The primary concern with facetectomy is that removing the facet joint eliminates an important stabilizing structure. Extensive facetectomy may create or worsen spinal instability, potentially necessitating fusion surgery to restore stability.1

Spinal fusion: Fusion procedures aim to eliminate motion at the affected spinal segment by permanently joining adjacent vertebrae. Bone graft material, often supplemented with metal hardware such as screws and rods, is used to create a solid bony bridge between vertebrae. By eliminating motion, fusion theoretically eliminates facet joint pain.

Spinal fusion has been performed for decades and can provide pain relief in appropriately selected patients. However, fusion procedures have significant drawbacks. They involve substantial surgical dissection and tissue trauma, require prolonged recovery periods of several months, permanently eliminate motion at the fused segment, increase stress on adjacent spinal levels and may accelerate adjacent segment degeneration, and carry risks including nonunion (failure of fusion), hardware complications, infection, and persistent pain.12

Modern spine surgery philosophy increasingly emphasizes motion preservation when possible, making fusion a less desirable option for many patients.

Radiofrequency ablation (RFA): This minimally invasive procedure uses radiofrequency energy to generate heat, creating thermal lesions that interrupt pain signal transmission from the medial branch nerves supplying the facet joints. RFA is performed as an outpatient procedure under local anesthesia with fluoroscopic guidance.

The electrode is positioned adjacent to the medial branch nerve, and radiofrequency current is applied for 60-90 seconds, heating the tissue to temperatures that destroy nerve function. Pain relief typically develops gradually over several weeks as the damaged nerves cease transmitting pain signals.

RFA can provide significant pain relief lasting six months to two years or longer in successfully treated patients. Research demonstrates that properly performed RFA provides meaningful pain reduction in approximately 70% of patients with confirmed facetogenic pain.13

However, traditional RFA has limitations. Nerves can regenerate over time, leading to recurrent pain that may require repeat procedures. The heat generated during RFA can cause collateral damage to surrounding tissues. The thermal lesions created are relatively small, and incomplete nerve ablation may result in inadequate pain relief.1

Endoscopic and minimally invasive techniques: Advances in endoscopic spine surgery have enabled surgeons to address facet joint pathology through very small incisions using specialized instruments and cameras. Endoscopic approaches offer advantages including reduced tissue disruption, faster recovery, and the ability to directly visualize and treat pathology. Recent research has explored endoscopic techniques for facet joint debridement, synovectomy, and osteophyte removal.13

While these techniques show promise, long-term outcome data remain limited compared to traditional open procedures.

Advanced Treatment at Deuk Spine Institute

At Deuk Spine Institute, we have developed innovative procedures that address the limitations of traditional surgical approaches while providing definitive relief for facet joint disease.

Deuk Plasma Rhizotomy® (DPR)

Deuk Plasma Rhizotomy® represents a significant advancement over traditional radiofrequency ablation. This procedure uses plasma energy rather than radiofrequency heat to permanently block pain signals from the nerves supplying the facet joints.

Unlike conventional RFA, which creates thermal lesions that damage surrounding tissue and allow nerve regeneration over time, DPR® uses a precisely controlled plasma field to selectively target and permanently deactivate the medial branch nerves. The plasma energy creates a more complete and permanent nerve lesion while minimizing collateral tissue damage.

The procedure is performed through a 4-millimeter incision under twilight sedation. Using advanced image guidance, surgeon, Dr. Ara Deukmedjian, navigates to the exact locations of the medial branch nerves supplying the painful facet joint. The plasma energy permanently blocks pain signal transmission, providing lasting relief.

Key advantages of Deuk Plasma Rhizotomy® include permanent elimination of facetogenic pain with a single treatment in 99% of properly selected patients, minimal tissue disruption through a 4-millimeter incision, minimal blood loss averaging less than 3 milliliters, outpatient procedure with discharge within 23 hours, return to normal activities the next day with no postoperative restrictions, no narcotic pain medications required, and preservation of joint motion and spinal stability.

Deuk Plasma Rhizotomy® has been successfully performed on hundreds of patients over multiple years without a single surgical complication. The procedure can be applied to cervical, thoracic, and lumbar facet joints, as well as sacroiliac joints and other arthritic joints throughout the body.

Deuk Laser Disc Repair® (DLDR)

For patients whose facet joint disease occurs in conjunction with disc pathology—a common scenario given the integrated nature of the spinal motion segment—Deuk Laser Disc Repair® addresses both pain-generating components.

This innovative procedure uses precision laser technology to treat damaged disc tissue that contributes to abnormal facet joint loading. By addressing the underlying disc pathology, stress on the facet joints is reduced, which may provide relief even when facet degeneration is present.

Deuk Laser Disc Repair® preserves the disc rather than removing it, maintains normal spinal motion rather than eliminating it through fusion, involves minimal tissue disruption, and provides lasting relief by treating the root cause of pain rather than simply masking symptoms.

For patients with combined disc and facet pathology, a comprehensive approach that addresses both pain generators may be necessary. At Deuk Spine Institute, we carefully evaluate the entire motion segment to identify all sources of pain and develop treatment plans tailored to each patient’s specific pathology. Find out if you are a candidate for our minimally invasive procedures by uploading your latest MRI for a free virtual consultation and review with Dr. Ara Deukmedjian.

Patient Selection and Surgical Candidacy

Not every patient with facet joint disease requires or would benefit from surgical intervention. Appropriate patient selection is crucial for achieving optimal outcomes. Surgery may be considered when conservative treatment has been appropriately implemented without adequate relief, diagnostic injections confirm the facet joints as the primary pain source, symptoms significantly impair quality of life and functional capacity, and the patient is medically appropriate for the proposed procedure and has realistic expectations about outcomes.

Conversely, surgery may not be appropriate for patients who have not undergone adequate conservative treatment, those with primarily psychological or psychosocial pain drivers, individuals with unrealistic expectations, or those with medical comorbidities that create unacceptable surgical risks.

A comprehensive evaluation by a qualified spine specialist is essential to determine whether surgery is appropriate and, if so, which procedure is most suitable for your specific condition.

Prevention Strategies and Long-Term Management

While facet joint degeneration cannot be entirely prevented, especially given the role of aging, several strategies can help minimize risk and slow progression.

Maintaining Spinal Health

Regular exercise: Engaging in activities that strengthen core muscles and maintain flexibility helps support proper spinal mechanics. Low-impact aerobic exercises such as swimming, cycling, and walking promote overall fitness without placing excessive stress on the facet joints.

Proper body mechanics: Using correct lifting techniques, avoiding prolonged static postures, and maintaining good posture during daily activities reduces cumulative stress on facet joints.

Ergonomic optimization: Proper workstation setup, supportive seating, and appropriate desk and computer positioning minimize postural strain during occupational activities.

Weight management: Maintaining a healthy body weight reduces mechanical loading on the spine, particularly important for lumbar facet joints.

Early Intervention

Addressing spinal symptoms early, before chronic changes develop, may prevent progression to more severe facet joint disease. If you experience persistent back or neck pain, seeking evaluation from a healthcare provider can lead to early diagnosis and appropriate treatment.

Monitoring and Follow-Up

For patients who have undergone treatment for facet joint disease, regular follow-up helps ensure sustained improvement and allows early detection of any recurrence or progression. Continued adherence to exercise programs and lifestyle modifications is essential for long-term success.

Understanding Your Options and Making Informed Decisions

Facet joint disease is a complex condition that requires accurate diagnosis and individualized treatment planning. While the condition is common and often progresses with age, effective treatment options are available across the spectrum from conservative care to advanced surgical interventions.

If you are experiencing chronic neck or back pain that has not responded adequately to initial treatment measures, a thorough evaluation by a spine specialist can determine whether facet joints are contributing to your symptoms. At Deuk Spine Institute, we offer comprehensive diagnostic services, including a free virtual MRI review and consultation to help identify the source of your pain and develop an optimal treatment strategy.

Our advanced minimally invasive procedures, including Deuk Plasma Rhizotomy® and Deuk Laser Disc Repair®, represent significant advances over traditional spine surgery. These techniques provide definitive relief while preserving spinal anatomy and function, with minimal recovery time and exceptional safety profiles.

Understanding your condition empowers you to make informed decisions about your care. We encourage you to explore all available options, ask questions, and actively participate in developing your treatment plan.

TLDR: Facet Joint Disease Explained Simply

Facet joint disease is one of the most common causes of chronic neck and back pain, resulting from degeneration and inflammation of the small stabilizing joints at the back of the spine. These joints, which normally guide spinal movement and distribute forces, can break down over time due to aging, injury, disc degeneration, poor posture, and other factors. Symptoms typically include localized back or neck pain that worsens with extension and prolonged standing, referred pain to the buttocks and thighs, morning stiffness that improves with activity, and reduced range of motion. The condition is diagnosed through clinical examination, imaging studies, and diagnostic injections that confirm the facet joints as pain generators.

Conservative treatments, including physical therapy, medications, lifestyle modifications, and therapeutic injections, are appropriate initial management for most patients. When conservative care fails to provide adequate relief, surgical options are available. Traditional approaches include radiofrequency ablation, facetectomy, and spinal fusion, each with specific advantages and limitations. Modern minimally invasive techniques such as Deuk Plasma Rhizotomy® offer significant advances over traditional surgery, providing permanent pain relief through a 4-millimeter incision with same-day discharge and next-day return to activities. For patients with combined disc and facet pathology, procedures like Deuk Laser Disc Repair® address multiple pain sources while preserving spinal anatomy and function. The key to successful outcomes is accurate diagnosis, appropriate patient selection, and individualized treatment planning based on each patient’s specific pathology and goals.

FAQs

Q: What is the difference between facet joint disease and facet joint arthritis?

A: These terms are essentially synonymous and are often used interchangeably. Facet joint disease, facet arthropathy, and facet joint arthritis all refer to degenerative and inflammatory changes within the facet joints of the spine. The condition represents a form of osteoarthritis that specifically affects these small spinal joints. Some practitioners use “facet joint disease” as a broader term that encompasses the full spectrum of facet pathology, while “facet arthritis” more specifically emphasizes the arthritic, degenerative nature of the condition. Regardless of terminology, the underlying pathology involves cartilage breakdown, inflammation, and progressive structural changes within the facet joints.14

Q: How can I tell if my pain is coming from facet joints versus discs?

A: Distinguishing facet-mediated pain from discogenic pain based on symptoms alone can be challenging, as there is considerable overlap. However, certain characteristics may suggest facetogenic pain. Facet joint pain typically worsens with extension (backward bending), prolonged standing, and rotational movements, while often improving with flexion and sitting. The pain is usually localized to the back or neck and may refer to the buttocks, hips, or thighs, but rarely extends below the knee. Morning stiffness that improves with gentle activity is common. In contrast, discogenic pain often worsens with flexion activities, such as bending forward, prolonged sitting, and coughing or sneezing. Disc-related pain may radiate further down the leg in a dermatomal pattern if nerve root compression is present. Ultimately, a definitive determination requires diagnostic evaluation, including imaging studies and, often, diagnostic injections to identify the true pain source. Many patients actually have both disc and facet pathology contributing to their symptoms, requiring comprehensive evaluation of the entire motion segment.1

Q: Can facet joint injections cure my condition, or do they just provide temporary relief?

A: Facet joint injections, whether intra-articular injections directly into the joint or medial branch blocks targeting the nerves supplying the joint, are primarily therapeutic rather than curative. These injections typically combine a local anesthetic for immediate pain relief with a corticosteroid medication to reduce inflammation. The relief provided usually lasts from several weeks to several months, depending on the individual response and the severity of the underlying pathology. The injections do not repair damaged cartilage or reverse degenerative changes within the joint. However, they can serve important purposes: confirming the diagnosis by determining whether the facet joint is truly the pain source, providing a window of pain relief that allows patients to participate more effectively in physical therapy and exercise programs, and offering symptomatic relief for patients who are not surgical candidates or who prefer to avoid surgery. Some patients achieve sustained benefit from injections combined with rehabilitative exercise, while others experience diminishing returns with repeat injections over time. For patients who obtain good but temporary relief from diagnostic injections, more definitive treatments such as radiofrequency ablation or Deuk Plasma Rhizotomy® may provide longer-lasting or permanent pain relief.11

Q: At what point should I consider surgery for facet joint disease?

A: The decision to pursue surgical treatment is highly individual and depends on multiple factors. Surgery becomes a reasonable consideration when you have completed an appropriate trial of conservative treatment—typically three to six months of physical therapy, medications, activity modifications, and potentially injections—without achieving adequate pain relief; your symptoms significantly interfere with your daily activities, work, or quality of life despite conservative management; you experience progressive symptoms or neurological deficits; diagnostic injections confirm that facet joints are the primary source of your pain; you are medically appropriate for surgery with realistic expectations about outcomes and recovery; and you prefer a more definitive solution rather than ongoing conservative management. It is important to note that surgery is not urgent in most cases of facet joint disease. This is typically an elective decision that you can make after careful consideration and thorough discussion with your healthcare providers. The exception would be if you develop severe neurological symptoms such as progressive weakness, bowel or bladder dysfunction, or other signs of significant nerve compression—these situations may require more urgent intervention. At Deuk Spine Institute, we believe that patients deserve comprehensive education about all available options, from conservative care to advanced surgical techniques. We encourage you to take advantage of our free consultation and MRI review service to receive an expert evaluation of your specific condition and recommendations tailored to your individual situation.

Q: Is it possible to have facet joint disease at multiple levels of my spine?

A: Yes, multilevel facet joint disease is extremely common. Degenerative changes affecting facet joints frequently occur at multiple spinal levels simultaneously, particularly in the lower lumbar spine, where mechanical stresses are greatest. Research demonstrates that facet arthropathy often progresses in a relatively predictable pattern, with the L4-L5 and L5-S1 levels most commonly affected in the lumbar spine, followed by L3-L4. Similarly, in the cervical spine, the lower cervical levels are most frequently involved. The presence of facet disease at one level increases the likelihood of pathology at adjacent levels over time, as altered biomechanics and compensatory mechanisms place additional stress on nearby motion segments. When evaluating patients with suspected facetogenic pain, spine specialists carefully assess all spinal levels to identify all potential pain generators. Diagnostic injections can help determine which specific facet joints are contributing most significantly to symptoms. The presence of multilevel disease does not necessarily mean that all affected joints require treatment—often, one or two levels are primarily responsible for symptoms. Treatment planning for multilevel facet disease requires careful consideration of which levels are truly symptomatic versus which show degenerative changes on imaging but are not generating pain.3

Q: Can facet joint disease lead to other spinal problems?

A: Yes, facet joint disease can contribute to the development of other spinal conditions through several mechanisms. Advanced facet arthropathy with osteophyte formation can cause spinal stenosis, narrowing the spinal canal and compressing neural structures. Hypertrophied facet joints can narrow the neural foramina, leading to nerve root compression and radicular symptoms. Facet joint degeneration can contribute to segmental instability, particularly when combined with disc degeneration—this may progress to degenerative spondylolisthesis, where one vertebra slips forward relative to the one below. The altered biomechanics resulting from facet disease at one level can accelerate degeneration at adjacent levels, a phenomenon called adjacent segment disease. Chronic facet-mediated pain can lead to protective muscle spasm and abnormal movement patterns that place stress on other spinal structures. Additionally, facet joint disease and disc degeneration commonly coexist and influence each other’s progression—the loss of disc height alters facet joint mechanics, while facet instability can accelerate disc breakdown. This interconnected nature of spinal pathology underscores the importance of comprehensive evaluation and treatment that addresses all components of the affected motion segment rather than focusing narrowly on a single structure. At Deuk Spine Institute, our diagnostic approach examines the entire spine to identify all sources of pain and factors contributing to your symptoms, allowing the development of a treatment plan that comprehensively addresses your specific pathology.1

Sources

1: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/books/NBK441906

2: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK541049/

3: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9719706/

4: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6206372/

5: https://deukspine.com/blog/bone-spurs-root-cause-of-and-symptoms

6: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23147891/

7: https://deukspine.com/blog/degenerative-disc-disease

8: https://sportsmedicine.mayoclinic.org/condition/facet-arthritis/

9: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11595282/

10: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10764212/

11: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17256032/

12: https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/procedures/si-sacroiliac-joint-fusion